The Textual City

In the age when cities developed around central squares or plazas and when people lived within limits prescribed by regional societies, the central square was the nucleus of communication, and the cathedral, the castle, and the city hall were the spiritual supports, as well as the symbols of urban life. Horses and carriages moving along radial streets past rows of buildings must have formed a very harmonious ensemble.

Kenzo Tange[1]

Historically, cities have structured themselves around the material flows due to current technological paradigms in communication and transportation—essentially techniques of production, modes of consumption and means of exchange; the ways in which business is done and societies are organized. The city as space of place was unified by these social cultural relations and discourse, fostering a union among a group people committed and tied to that place.

The ancient city was representational; things of a collective nature took place there and the city's spatial organization reflected those activities.[2] Based on a polar coordinate system at the intersections of crossroads, cities developed around points of juncture and were defined by the church, market and public square where people interacted on a political, social, economic and cultural level. The way people communicated was radically altered with the advent of the printing press, which marked a crucial break in the methods used to convey information, both verbal and visual.[3] Printing technology from the hand-scripted illuminated manuscript to the printed book altered techniques of book production, which consequently affected the way information was organized and disseminated, how people were educated, and the way society was structured.[4] For example, prior to the newspaper, sermons in churches were coupled with news about local and foreign affairs. Eventually the newspaper began to replace the pulpit and its forum for congregation, allowing churchgoers to learn about local affairs in silence at home, which resulted in a restructuring of urban social relations.[5]

The Enlightenment with its reliance on scientific rationality marked a distinct shift from the medieval body-centered polar coordinate system[6] to the endless Cartesian grid of modern science.[7] This rationalization, again, can be seen by comparing the printed book with the hand-printed manuscript: publishers and editors began to be more concerned with the organization of the printed material to systematically index, catalogue and list information alphabetically over the quality of the scribe's calligraphy. Furthermore, the use of typography for texts and xylography for illustrations made it possible to produce identical text and images, maps and diagrams which could then be viewed simultaneously by scattered readers. This in itself constituted a communications revolution.[8]

Coordinating information in turn affected the constructed world and the organization of cities, which can be seen by contrasting the development of an ancient city versus a more modern one. For example, London, the ancient Roman city and later medieval trading settlement, began as a port on the Thames River and was organized according to a body-centered polar coordinate system; characteristic of a medieval town, its streets radiate from its center. Las Vegas, on the other hand, was established in 1905 as an eastern gateway to Los Angeles along the popularly-travelled northwest-oriented Old Spanish Trail, the main diagonal that bisects the city; representative of postmodern urbanism, it was planned using an orthogonal grid that extends infinitely into the desert. The layout of Las Vegas demonstrates the endless Cartesian frame and the rationalization of urban space. Today, Las Vegas is more destination than either gateway or crossroads with an un-centered center functioning like a node in a network of global connections.

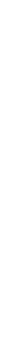

While the first true automobile may have been invented in Europe, the first large-scale production of automobiles in America was by Ransom Olds in 1902. By 1914, Henry Ford's production methods made the car affordable to the general population, dramatically altering the way cities were conceived. No longer grounded as either points at intersections of commerce or as points on a grid, futuristic cities were being imagined by visionaries like Moses King as four-dimensional spaces of flows defined by modes of transportation both horizontally and vertically, differentiated by rates of speed from pedestrian to automobile, train and airplane (figure 1). Within this layering of transit mobility, multivalent layers of communications technology were also being considered by architects as a means to guide the planning of cities on a global scale.

Figure 1. Richard Rummell, delineator, "King's Views of New York" cover plate illustration for King's Views of New York, published by Moses King, 1911.

The Mobile City The technical inventions that are today at the service of humanity will play a great role in the construction of future city-ambiences… The possibilities of the cinema, of television, of radio, of rapid travel and communications have not been utilized, and their effect on cultural life has been the most miserable. The exploration of technology and its utilization for higher ends of a ludic nature is one of the most urgent tasks for bringing about the creation of a unitary urbanism at the scale that future society demands.

Constant Nieuwenhuys[9]

The devastation wrought on Europe due to the Second World War brought about a complete reconsideration of the city by architects and artists worldwide. According to Constant Nieuwenhuys, Frankfurt in 1951 was indescribable: "Every morning I took my son to school. The walk to the school was across an enormous bombsite. A great heap of rubble, with here and there some places that had been flattened so you could walk over them like paths. It was a surreal landscape, and it inspired me enormously. If you walk through a town that lies in ruins, then the first thing you naturally think of is building."[10]

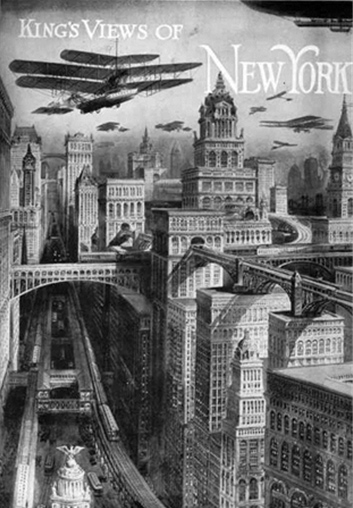

Figure 2. Constant Nieuwenhuys, New Babylon, project, Netherlands, 1958-74.

A 20th-century painter, architect and founding member of the Situationist International, Constant is perhaps best known for his ambitious project of unitary urbanism, New Babylon (figure 2), a city of continuity envisioned to cover the globe, disintegrating boundaries, frontiers and political lines. This proposed city was intended to prompt its citizens to express their creativity through their constant reconfiguration of its open and malleable living space.[11] Constant's unitary urbanist theory is primarily concerned with the emotive affect of dynamic material space on its inhabitants: impermanent and metamorphosing spatial relations that disintegrate all boundaries between public and private, work and leisure—curiously prefiguring the restructuring of space occurring today due to the proliferation of information technology and electronic media.

Based on the ludic notion of play, New Babylon is similar to the ancient labyrinth, with its spirit of movement and negotiation which encourages spatial disorientation and confusion, in contrast to the kind of openness and transparency favored by early modern architects.[12] The labyrinth is a space of continuity, where each space, each passageway, each thoroughfare, is directed to action, progress, chance and surprise. As described by Constant in speaking for the Situationists, "…our conception of urbanism is therefore above all dynamic. We also reject the establishment of buildings in a fixed landscape that now passes for the new urbanism." [13]

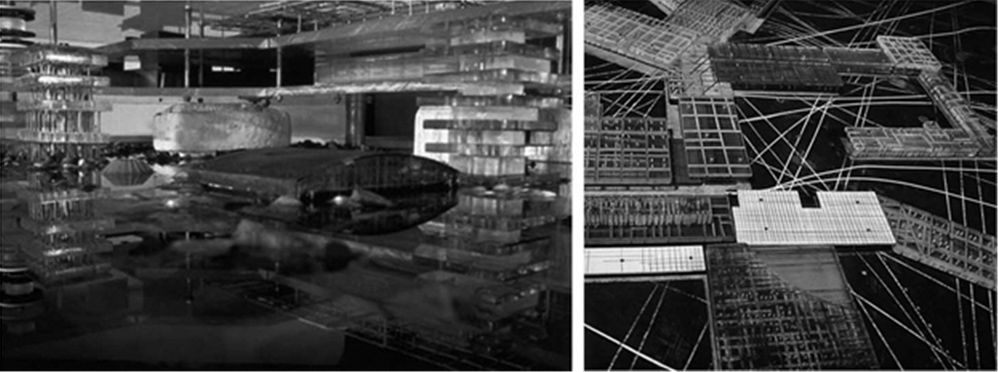

The opposite of Constant's labyrinthine New Babylon is characteristic contemporary functionalist urbanism, which is based on static, sedentary and utilitarian principals, dedicated to the isolation of separate and disparate practices; and like the Cartesian grid is ordered, knowing and controlling. While guided by the dynamism inherent in 20th century urban transportation systems, a rational example of the "new urbanism" critiqued by Constant might be Paul Rudolph's Lower Manhattan Expressway (LME), which integrates multiple modes of mobility into the urban fabric by submerging transit systems and constructing a pedestrian city of light and air above (figure 3). While the LME organizes the various means of transportation spatially and temporally as one design solution to Robert Moses' planning vision for NYC, it likely would have similarly segregated the city into areas of "haves" and "have-nots" as Moses' urban planning eventually succeeded in doing with the Cross-Bronx Expressway. In contrast, Constant's transformative, mobile city offers more opportunity for diversity in the play of urban life.

Figure 3. Paul Rudolph, Lower Manhattan Expressway, project, New York City, 1967-72. From this entrance near the Holland Tunnel, the Brooklyn and Williamsburg Bridges can be seen beyond.

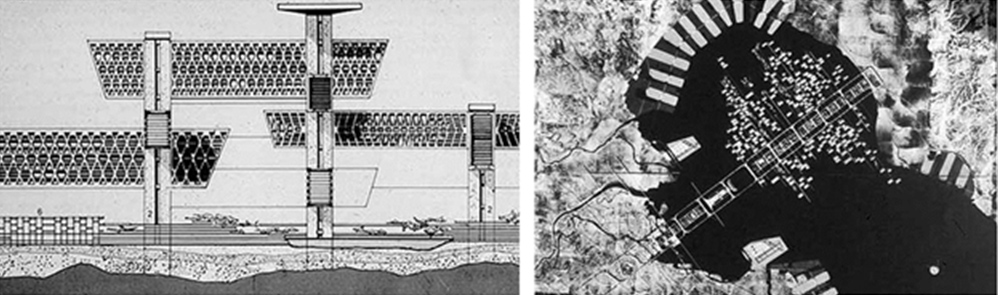

In 1950, New York City was the only megacity in the world, which is a city with over 10 million inhabitants. Tokyo's population was verging on 10 million in 1960 when Kenzo Tange proposed the Tokyo Expansion Plan (figure 4). Tange's scheme was predicated on mass movement, speed and automated communication.[14] In the modernist Cartesian tradition, Tange's scheme was linear: the civic axis crossing Tokyo Bay organized the city horizontally based on the spontaneous flow of contemporary society with a core system for vertical transportation of people and services in single shafts forming the nuclei of buildings. Based on the "flowing mobility" of the "speed and scale of movement in the city", the goal of this system was to provide a "new order" to the city.[15] Tange's scheme had both a spatial order and a speed hierarchy through the vertical organization of mass transit, car and pedestrian traffic, but "was widely criticized for its technological determinism and axial monumentality".[16] Although as a member of the Japanese Metabolist Group Tange approached the city as a living organism subject to a continuous cycle of growth and metamorphosis responsive to dynamic patterns of urban flow and changing function, his linear Tokyo Expansion Plan was still bound by the constraints of the grid and the limits of Tokyo Bay.

Unrestrained by geographical limits, New Babylon is a wholly constructed artificial world, supported by computerized-technology that anticipates the hypertextual spatial relationships presently unfolding in a world striving to keep up with its own technology. This covered city is intended to be a global network of mega-structures, divided into sectors, suspended high above the ground, to support all forms of mobility. Based on Constant's "ludic solutions"[17] to urban planning problems and the infinite possibilities afforded by the notion of child's play, the structure itself is a mobile entity that can continuously transform to the desires of its occupants.

Figure 4. Kenzo Tange, Tokyo Expansion Plan, project, 1960.

Prefiguring Manuel Castells' 1989 "space of flows,"[18] New Babylon was founded on the transformative capacity of technology and its potential to create new states of being. Because New Babylon would cover the natural landscape with a multi-leveled lay-out of an impermanent network of units, linked one to the other in chains that could develop or be extended in every direction, the city's plan is spatially and temporally four-dimensional and indeterminate, confounding the Cartesian grid. Although the sectors would exist autonomously, they would inter-communicate so that the perception from within the city would be one of spatial continuity, without national boundaries. More like a nomadic culture, New Babylon would function in a permanent state of transformation so that life according to Constant would be "an endless journey across a world that is changing so rapidly that it seems forever other".[19]

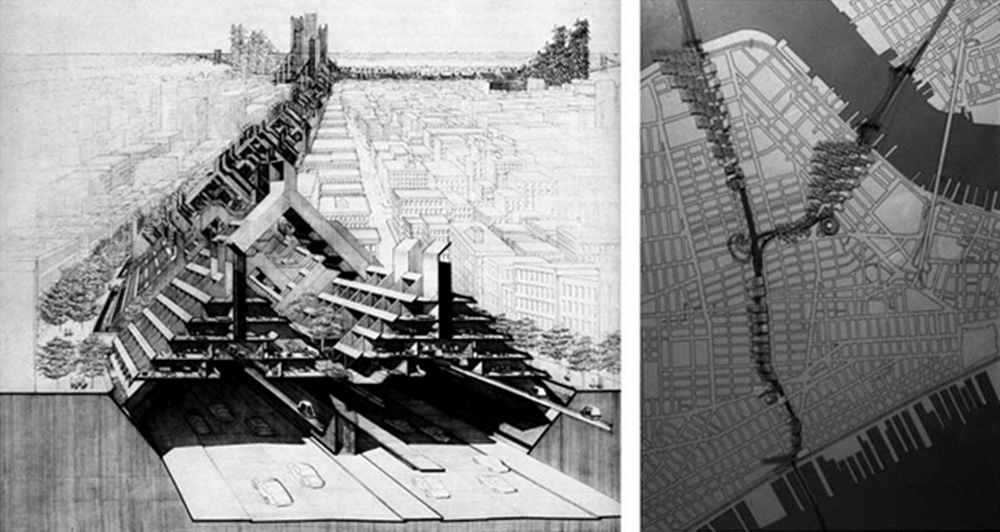

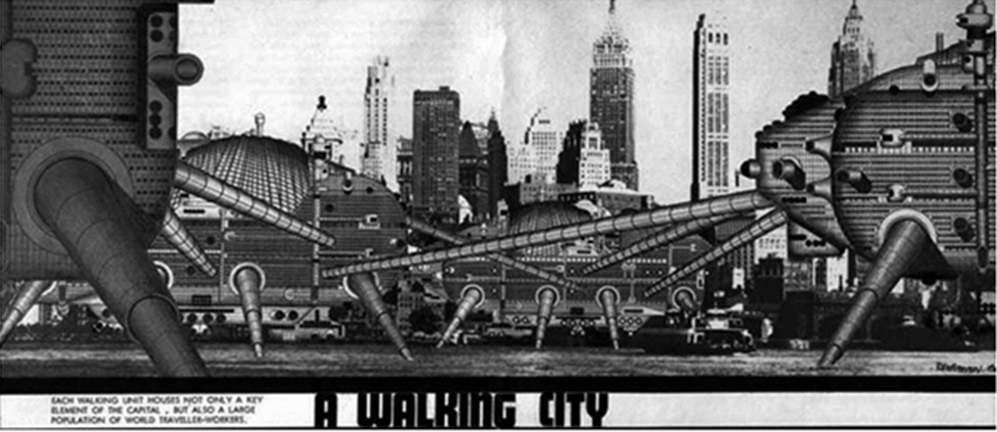

Like the artist Constant, Archigram completely reconsidered the modernist project and represented ideas as speculative works of art. To this group of six architects, the building was a ghostly reminder of all the on-going processes—economic, technical and social—that make up the environment in which it was produced. Forecasting today's technological society, they regarded the world as a continuous building site. A Walking City (figure 5) represents a "new agenda where nomadism is the dominant social force: where time, exchange and metamorphosis replace stasis; where consumption, lifestyle and transience become the program; and where the public realm is an electronic surface enclosing the globe"[20] (author's emphasis).

Inspired by Archigram, in 1969 the architects Alan Boutwell and Michael Mitchell proposed a gigantic, continuous linear city of one million inhabitants to span from San Francisco through Des Moines, Chicago and Detroit to New York City.[21] It went straight across the American continent on one-hundred meter high pillars. Its interior combined all the classical functions of urban life and was connected by a complex traffic system that was differentiated by speed, transportation and distances; included was parking on the lowest level, services on the intermediate, residential on the upper strata, topped by an air landing strip. While it may have been sensational at the time, Boutwell and Mitchell's scheme was still a modernist project like the functionalist urbanism objected to by Constant. Their rational scheme was linear and textual in contrast to Archigram's visions, which anticipated the future. Based on a four-dimensional transformative spatiality, both A Walking City and New Babylon are hypertextual: like nodes in a network, a reconfigurable text and changing landscape capable of encompassing the globe.

Figure 5. Warren Chalk and Ron Herron, A Walking City, project, England, 1964.

The Hypertextual City In this ideal text the networks are many and interact, without any one of them being able to surpass the rest; this text is a galaxy of signifiers, not a structure of signifieds; it has no beginning; it is reversible; we gain access to it by several entrances, none of which can be authoritatively declared to be the main one...

Roland Barthes, S/Z[22]

Analogous to the grid is text, derived from the Latin word for weaving and for interwoven material.[23] Similarly is concordance, an alphabetical list of the principal words used in a book or body of work, with their immediate contexts. The electronic linking which has reconfigured text as we have known it has created a hypertext: a form of textuality that permits multilinear reading paths—prefigured by medieval works such as the Byzantine Talmud, a book with pages comprised of marginalia and texts within texts.[24] Hypertext is a conceptual framework of networked links in the electronic realm that has reconfigured access to textual and image-based information. With the potential to reveal multivalent levels of information, like the labyrinth, hypertext can be opaque and confusing.

There are two types of labyrinths: the unicursal labyrinth with origins in the visual arts and the multicursal labyrinth from the literary tradition.[25] The unicursal model describes the longest, most circuitous route between two points of certainty: entrance and center. There are no choices, one can merely go forward or backward; the maze-walker goes where the path leads without fear of getting lost. The multicursal model incorporates an extended series of bivia, or an array of choices; one risks getting lost and remaining perpetually imprisoned. Each fork or alternative requires a pause for thought and decision. While being in the labyrinth may be bewildering, when seen from above the labyrinth in plan reveals the inextricable prison to be a simple, well-ordered concentric structure.

Hypertext has changed relationships between reading and writing, has altered demarcations between the inside and outside of the text, and has changed the nature and role of narrative. Hypertext is a mode of communication with the potential to articulate the sociality of the internet, and to democratize and empower the individual. It can be distinguished from traditional text by its non-linearity—it is inherently spatial. The links in hypertext can connect disparately-located bits of information, image and text; information can be found within information.[26] Considered spatially, communication becomes a virtual world of hyperspace where one can walk alone through a meadow, step behind a tree, open a door into a crowded room, look out a window toward a meadow and find oneself in city traffic. Here architecture exists within architecture, cities within rooms, rooms within cities and worlds within worlds.

Anticipated over fifty years ago by visionary architects, the virtual world of hyperspace has become an alternative reality for many through present-day social media. For example, virtual social worlds allow inhabitants to choose their behavior and essentially live a virtual life similar to their real life. Virtual social world residents can interact in a three-dimensional virtual environment, which allows for an unlimited range of self presentation strategies that usually closely mirrors the one observed in real life settings.[27] In contrast to the global flow of playful human interaction anticipated by Constant's New Babylon and Archigram's A Walking City is the potential for the virtual social world resident to stay home and supplant personal discourse and urban living with an imaginary reality. Social media in general has exploded as a category of online discourse where people create content, share it, bookmark it and network at a prodigious rate. Because of its ease of use, speed and reach, social media is fast changing the public discourse in society and setting trends and agendas in topics that range from the environment and politics to technology and the entertainment industry. In this way, social media is becoming a form of collective wisdom.[28]

On July 19, 2010 a blogger Khaled Said was brutally beaten to death and left in the street by Egyptian authorities. The "We are all Khaled Said" Facebook site created in summer 2010 amassed more than 600,000 fans and evolved into a central news hub for the Revolutionary Youth Council. This Facebook site was able to easily gather people in groups online when it was getting harder and harder to do so on the streets. Egypt's National Police Day, January 25, 2011 was chosen by these dissidents to publicly disdain rather than commemorate this security force known for a long history of brutality and human rights abuses.

After two weeks of protests, Hosni Mubarak resigned as President of Egypt the following February 11, his regime toppled by a counter insurgency led by a group of 14 tech-savvy Egyptians who used social media, secrecy and strategic maneuvering to counter Egypt's vast security apparatus. Realizing they were under surveillance by security, Facebook groups were used as a decoy, not as the primary means of organization. The activists went back to the original social network: face-to-face communication. After three days the government had cut off all means of communication, including mobile phone networks and the internet. The true locations of meeting points were only discussed in person and could be changed quickly in fewer than five minutes via an informal land-line telephone network. As a result, the police were caught off guard, spreading out in massive numbers in the wrong locations around Cairo. Twitter and Facebook were used to direct larger crowds, but only once protesters were actually set in place, marching on the streets.[29]

The events that took place in the streets of Cairo demonstrate that in spite of today's seeming "space of flows" connecting distant locales around shared functions and meanings due to a technology of electronic circuits and fast transportation corridors, people are still very much committed and tied to an embodied "space of place" unified by social cultural relations and discourse. In the end, the successful socio-political restructuring of this urban realm was due to a body-centered cultural exchange that occurred in tangible public space through direct social interaction.

Conclusion The spaces we inhabit, the social relationships we form, and our modes of perception have historically been influenced by the way we receive information. Like negotiating one's way through a labyrinth, reading the city is hypertextual and perspectival: its image unfolds through movement along a path, at each node there are alternatives which require reflection, there are many entrances and no right one, and there is an underlying order which can seldom be appreciated except at a distance. The past fifty years of imaginative architectural speculation is remarkably visionary. It is surprising how seemingly outlandish ideas can forecast future realities. No, there are no walking cities. And, yes, it would be wonderful if there were indeed a unitary urbanism, because that would predicate the elimination of borders and boundaries and hopefully political unrest. On the other hand, present-day reality is a global exchange of information through dynamic digital interaction. As a result, the "space of flows" may, indeed, be disruptive, but productive. The idea of the city may restructure itself toward a more global unitary urbanism made possible through new modes of production, consumption and exchange as a result of advanced communication technologies that are evolving faster than imaginable.

Endnotes

[1] Kenzo Tange, "A Plan for Tokyo, 1960: Toward a Structural Reorganization," in Joan Ockman, Architecture Culture 1943-1968 (New York: Columbia Books of Architecture/Rizzoli, 1993), 327-334.

[2] Alan Colquhoun, "The Superblock," Essays in Architectural Criticism (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1981), 83-102.

[3] Elizabeth L. Eisenstein, The Printing Press as an Agent of Change, vol. I (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1979).

[4] Lewis Mumford, Technics and Civilization (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc., 1963), 136-137.

[5] Eisenstein, 131-132.

[6] John M. Kennedy, Paul Gabias and Morton A. Heller, "Space, Haptics and the Blind," Geoforum 23/2 (1992): 175-189. Blind people navigate with respect to the body's position in absolute space, the reference point and point of origin continuously moving with respect to the body's location, a polar coordinate system whereby other locations are identified with respect to a central point.

[7] Stefan Polónyi, "The Concept of Science, Structural Design, Architecture," Daidalos 18 (15 Dec 1985): 33-45.

[8] Eisenstein, 52-53, 117.

[9] Constant Nieuwenhuys, "The Great Game to Come," (1959) in Ockman, 315.

[10] Linda Boersma, "Constant," BOMB 91 (Spring 2005), accessed: http://bombsite.com/issues/91/articles/2713

[11] Joan Ockman, Architecture Culture 1943-1968, 314.

[12] Jan Bryant, "Play and Transformation (Constant Nieuwenhuys and the Situationists)," Drain Magazine (2006) accessed: http://www.drainmag.com/ContentPLAY/Essay/Bryant.html

[13] Nieuwenhuys, 315.

[14] Ockman, 325.

[15] Tange, 328-329.

[16] Ockman, 326.

[17] Nieuwenhuys, ibid., 315.

[18] Manuel Castells, The Informational City: Information Technology, Economic Restructuring, and the Urban Regional Process (Oxford : Basil Blackwell, 1989).

[19] Constant Nieuwenhuys, exhibition catalogue (The Hague, Haags Gemeetenmuseum, 1974), 4.

[20] David Greene, "Prologue," in Concerning Archigram, edited by Dennis Crompton (London: Archigram Archives, 1999), 3.

[21] Alan Boutwell and Michael Mitchell, "Planning on a National Scale," Domus 470 (Jan 1969).

[22] Roland Barthes, S/Z trans. Richard Miller (New York: Hill and Wang, 1974), 5-6.

[23] George P. Landow, Hypertext: the convergence of contemporary critical theory and technology (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992), 21-22.

[24] James Elkins, The Domain of Images (New York: Cornell University, 1999), 101-103.

[25] Penelope Reed Doob, The Idea of the Labyrinth (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1994).

[26] Michael Benedikt, "Introduction" and "Cyberspace: Some Proposals," Cyberspace: First Steps (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1991). See also Marcos Novak, "Liquid Architectures in Cyberspace," in Cyberspace.

[27] Andreas M. Kaplan and Michael Haenlein, "Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media," Business Horizons 53/1 (January-February 2010), 59-68.

[28] Sitaram Asur and Bernardo A. Hubeman, "Predicting the Future with Social Media," 2010 IEEE/WIC/ACM International Conference on Web Intelligence and Intelligent Agent Technology, vol. 1 (2010), 492-499.

[29] Jon Jensen, "Behind Egypt's Revolution: Youth and the Internet," February 13, 2011 Global Post: http://www.globalpost.com/dispatch/egypt/110213/social-media-youth-egypt-revolution.